I know, I know. It’s been a while. I’m sorry Biley. Will you ever forgive me? (He probably won’t even read this). Cut to a little over 6 months after my last post and I’m finally making another post. I know this isn’t the post I promised months ago, but life got incredibly busy and other things took priority. But that’s not why you’re here, is it? Let’s dig right into the meat of the post: my entry to Jackie_Codes’ 2nd game jam. There were a few things I learned, a few things I noticed, a few things I wanted to discuss, and even something I wanted to brag about (humor me, I feel like we all secretly want to show off code we’re proud of).

Burnout: The Game

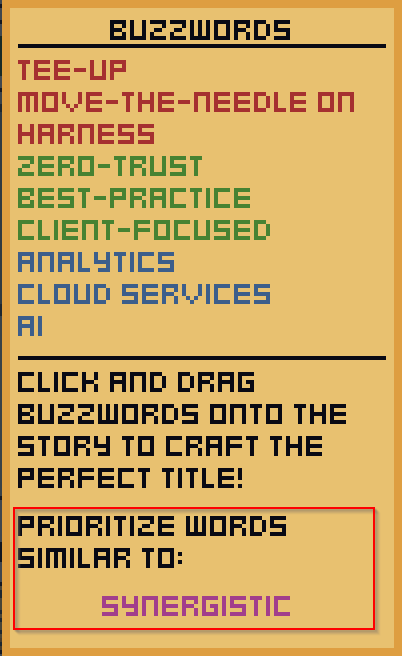

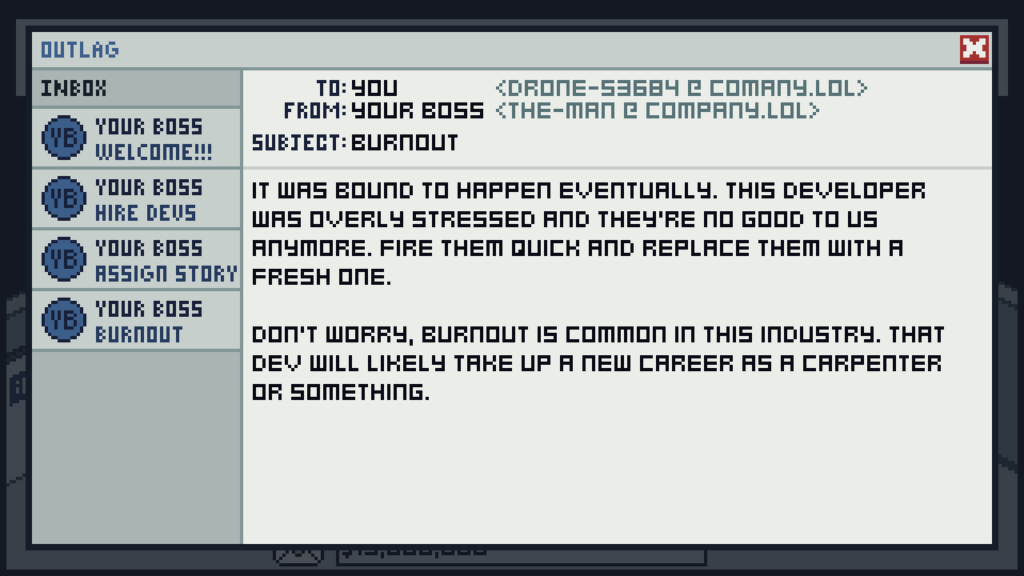

So first a quick overview of the game SolarLabyrinth and I made. As a newly hired Product Manager for The Company, it’s your job to hire developers and make sure their sprints are filled with plenty of tasks. Make sure your devs don’t have a single moment to spare lest you waste resources on your way to achieving your company’s IPO. Listen not to the noise complaints of the dev next to the bathroom, but instead to your heart as you craft artisanal user stories full to the brim with the very most refined of IT buzzword sludge. Stories are assigned a size at random, but the priority is proportional to how similar the target buzzword is to your story’s title. While completed story priority drives your company valuation up proportionally, it also drives up developer stress up, too! Raise your valuation enough to meet IPO before you run out of runway!

Jam Collaboration Takeaways

So with this being my 3rd game jam I wanted, as always, to try something new. One of the ways I challenged myself with this game jam was by entering the jam as part of a two person team. Now using the word “challenge” might initially might sound like the partner I worked with made more work for me than they helped, but if you’ll allow me, I think working as part of a team can be a double-edged sword. Yes, there are more people to help, more work hours, the possibility for division of labor, among many other benefits. I’ll cover a few potential issues that working as part of a team on a game jam can present and how my partner and I addressed (or ignored) each potential dilemma. And of course huge shoutout to SolarLabyrinth for partnering up with me for the jam!

Code Change Conflicts

The very first problem that pops into my head when working on a team is the potential for headaches when it comes to multiple individuals committing code to the repository simultaneously. Luckily for me, using Git as source control all but eliminates this problem. Anytime you try to push commits to the remote repository and you aren’t working with the latest changes, Git recognizes this and asks you to pull the latest changes before pushing your changes. Then when you pull the latest commits, Git will do all the work of merging your code changes with the changes made to the remote since your last pull. The only time that your intervention is needed is when you’ve made changes that conflict with changes made to the remote repository and Git can’t automatically determine the correct solution.

Having worked in the industry for over 10 years, I’m quite familiar with and comfortable handling Git merge conflicts, my only question was how often, if ever, would they occur? The answer? Literally only once did I ever have to complete a manual Git merge. Now the absence of conflicts could be for a few reasons: my coding habits, segmentation of tasks, and division of labor. I tend to try and commit and push often leading to very few of my individual changes being in direct conflict with the changes my partner was making. Both my partner and I tended to work on different mechanics which, naturally, can lead to changes being made to separate files which just inherently avoids conflicts. Finally, and we’ll discuss this next, but my teammate ended up focusing mainly on pixelart for the game and I nearly exclusively worked on the code which resulted in us making changes to completely different files, completely avoiding the problem altogether.

Differing Visions

My last main concern about doing a game jam with a team is the fear that I, or other teammates, won’t connect with the vision of the game concept that we settle on. Or even that picking a direction is challenging from the very start due to diverging visions. Luckily, however, Solar and I quickly settled on and both became enamored with the same idea. We agreed that the niche subject of the game was going to hurt our overall score (if you don’t understand at a deeper level the pain of kanban boards and Agile scrums, the game loses all therapeutic value), but we also agreed that didn’t matter as much as realizing our vision. This didn’t so much solve the issue of differing visions as it did allow both of us to hyperfocus on the task at hand. A win is a win, I suppose.

A Game Built Around the Mouse

“Fresh” on the heels of my last full post about drag and drop, we both felt like our vision of the drudgery and pain of corporate software development would be best served by a mouse driven interface. Dragging and dropping was something I was pretty familiar with and I didn’t see any reason to stray from that.

Challenging Myself with Pixelart

One of the ways in which I really truly challenged myself was with pixelart. Not being particularly inclined toward visual art I did challenge myself to make at least one art asset for this game. I did find that making a few of these inbox buttons for the email interface was something I could easily tackle. That being said, I wish I had challenged myself more and taken on a more difficult art task, as the contact logo was actually done by Solar, if I remember correctly, and I only really made the differing subject lines.

What I did learn from this is that, while I’m using the term “art” pretty loosely here cause I only really made text in these assets, pixelart doesn’t have to be quite as daunting a task as I had originally thought. In the future, I’d like to try to further stretch into the artistic side of development and tackle more challenging art.

Managing the Scope of the Project

Something that we really struggled with for this jam was finding the right balance of scope creep. Our passion for the subject matter drove us to excitedly pitch ideas while in the midst of development for features we’d love to integrate into the game, many of which made it into the final product, but many which didn’t make the cut. Finding that balance was incredibly difficult. I think it really played to my advantage that I had a partner to bounce ideas off of and help prioritize features. Without having that voice of reason to hold me accountable, I think I would have easily gotten besotted with any particular idea, wasting valuable time on a inane feature that wouldn’t have any measurable impact on the game.

Thanks Solar!

Controlling Node Visibility

Midway through the jam, I realized that Solar and I were going about hiding and showing control nodes completely differently. While I was modifying the .visible property of nodes, I found Solar was calling .show() and .hide(), which I didn’t know existed. Ultimately, this is an incredibly minor difference as even the documentation indicates that both solutions are equivalent. But it really highlights the importance of reading the documentation, something that I really think is generally undervalued. More than ever, knowing the capabilities of the nodes you’re using can save you so much time, work, stress, and headache.

Data Science

And now, if you’ve made it this far, we get to what I consider the real meat of this post: How I handled scoring the user stories. This is the part that I’m particularly proud of, but none of my work was particularly complicated or constrained to Godot. In reality, I wanted to leverage machine learning to score how similar the user story the player generated was to the randomly assigned “goal”. Now I didn’t want to have to wrestle with real-time analysis, especially given that the jam was going to be judged based on the web executables. Not to mention, real-time analysis would require that I either would need to find a proper natural language processing (NLP) library built for Godot or even more daunting, roll my own. Not exactly an enticing prospect for a game jam, unless that were the primary goal.

An NLP library that I had worked with somewhat extensively before was spaCy. By using this library, there is a simple way to determine how similar two words are to each other. The downside is that this library is for Python. But, having already resigned to not calculate similarity at runtime, this wasn’t really an issue. I did, however, need to find a way to determine at runtime a similarity score between two words. If not calculated at runtime, the next logical approach would be to precalculate the similarity scores so that they can be quickly and effortlessly retrieved at runtime.

Storage Limitations

I was a bit concerned about the storage constraints, as doing comparisons of every pair of words would grow with the square of our word list size. Doing some quick math:

- Given a list of 63 words

- Storing each score as an unsigned 8-bit integer

63 words × 63 words = 3,969 bytes

Having a resource file that’s 4kb is totally acceptable in my mind. Also 8 bits of precision feels decent. Now to explain how I decided on uint8. To be honest, I don’t have any super good reason. It’s a fairly common variable type so I felt confident that I could easily work with it. I went unsigned, because there’s never going to be a case where I’ll have a negative score so with an unsigned 8-bit integer I’ll have 0 to 255 for potential values and I thought this was an acceptable level of precision while still maintaining a fairly reasonable file size. In all honesty, I probably could have even gone with 64-bit integers, and it would have only been 8 times bigger, 32kb instead of 4kb.

Storing and Retrieving Scores

Given I’m concerned about storage constraints of the data file, I had to choose a file format that would add minimal overhead. I figured that the best overhead was no overhead and decided to go with a binary file. This was strictly based on absolutely no testing of any description but exclusively driven by my desire to challenge myself.

Given each score of two words is stored in a single byte, to calculate the address of each word pair, I use row-major order indexing meaning the byte address of any 2 words (given 63 words) will be at byte location:

byte location = indexword 1 × 63 + indexword 2

For example using the words “orchestrate” and “dynamic”:

address = 0 × 63 + 29

address = 29score = word_similarity("orchestrate", "dynamic")

score = 0.5818165093660355However, we need to convert that score to an 8-bit integer, so we multiply by 255:

score = 0.5818165093660355 × 255

score = 148Given a score of 148 and an address of 29:

![]()

File: similarities.tres

Initially, I thought to store the data I calculated in a .bin file, given it was simple binary data. However, I realized that both the Godot editor does not import .bin files nor do they get packaged into the executable. I might have simply been doing it incorrectly, but simply changing the file extension to .tres was enough to get the editor to import it and for the file to be packaged with the web build.

For those curious, here is the source that pregenerated the similarity scores:

import spacy

import json

# Make sure you install spacy and the word model

#> pip install spacy

#> python -m spacy download en_core_web_md

# Load the medium-sized English model (has word vectors)

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_md")

def word_similarity(word1, word2):

token1 = nlp(word1)[0]

token2 = nlp(word2)[0]

return (1 + token1.similarity(token2)) / 2

def example():

# Example usage

word1 = "orchestrate"

word2 = "dynamic"

score = word_similarity(word1, word2)

print(f"Similarity between '{word1}' and '{word2}': {score}")

def load_words(file_path="./data/user_story_data.json"):

with open(file_path, 'r') as file:

data = json.load(file)

return data

def write_uint8_to_file(filename, value, offset):

if not (0 <= value <= 255):

raise ValueError("Value must be an 8-bit unsigned integer (0-255)")

with open(filename, 'r+b') as f: # Open for reading and writing in binary mode

f.seek(offset)

f.write(bytes([value]))

def calculate_similarities(data_file="./data/similarities.tres"):

word_data = load_words()

word_list = word_data["verbs"]

word_list.extend(word_data["adjectives"])

word_list.extend(word_data["nouns"])

# Create or truncate file

open(data_file, "w")

ndx = 0

for word_a in word_list:

for word_b in word_list:

similarity = int(word_similarity(word_a, word_b) * 255)

try:

write_uint8_to_file(data_file, similarity, ndx)

except:

print(f'Similarity value between {word_a} and {word_b} has an invalid value: {similarity}')

exit()

ndx += 1

if __name__ == "__main__":

calculate_similarities()And if you’re curious about how I retrieved the data in Godot:

extends Node

const SIMILARITIES_FILE = "res://data/similarities.tres"

func get_similarity_values(positions: Array[int]) -> Array[float]:

var file := FileAccess.open(SIMILARITIES_FILE, FileAccess.READ)

var result: Array[float] = []

for position in positions:

file.seek(position)

var value = file.get_8()

result.append(value / 255.0)

return result

func get_similarity_value(position: int) -> float:

return get_similarity_values([position])[0]

func get_user_story_data() -> Variant:

var file = FileAccess.open("res://data/user_story_data.json", FileAccess.READ)

return JSON.parse_string(file.get_as_text())

func get_user_story_word_list() -> Array[String]:

var content: Variant = get_user_story_data()

var word_list: Array = content['verbs']

word_list.append_array(content['adjectives'])

word_list.append_array(content['nouns'])

var result: Array[String] = []

result.assign(word_list)

return result

func determine_similarity_position(word1: String, word2: String) -> int:

var content := get_user_story_word_list()

var ndx = 0

for first in content:

if first != word1:

ndx += content.size()

continue

for second in content:

if second == word2:

return ndx

ndx += 1

return -1

func determine_story_score(user_story: UserStory, target_word: String) -> float:

var indices: Array[int] = []

indices.append(determine_similarity_position(target_word, user_story.verb))

indices.append(determine_similarity_position(target_word, user_story.adjective))

indices.append(determine_similarity_position(target_word, user_story.noun))

var values := get_similarity_values(indices)

return values[0] + values[1] + values[2]